Tera Hofmann's Next Opponent: Retirement

Former professional goaltendtender Tera Hofmann looks back, and looks ahead.

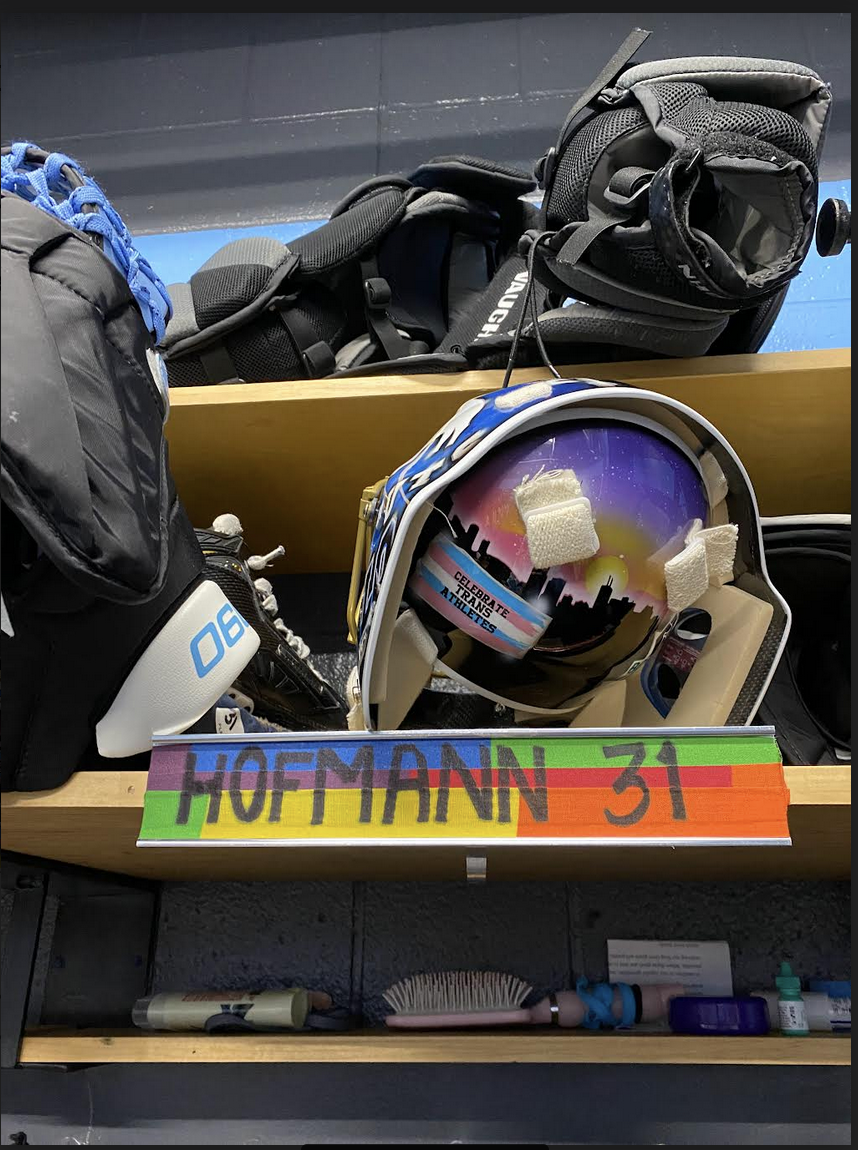

Tera Hofmann was a professional hockey player in the Premier Hockey Federation (formerly NWHL) for three seasons. She is dedicating this article to all players, staff, and fans who were not included in the new iteration of professional hockey in North America.

My parents did not grow up playing hockey. Their families were not concerned with things seemingly as trivial as extracurriculars. My maternal grandfather bought off-brand clothing and purchased paint on sale. He once told my mom that if she wanted to play sports, she’d better find someone to drive her. My paternal grandma worried about getting food on the table. She maneuvered the 1950s business world during the day and raised three kids solo in the evenings. So when six-year-old me decided I wanted to play hockey, my parents were naturally unsure of how to navigate this new territory. Nonetheless, I was enrolled in House League.

In the orangey light of my living room the night before my first game, my sister and I played “dress up” with our newly acquired hockey gear; pulling on our shin pads, trying to attach our socks, making sure a back jersey-tuck looked better than a front jersey-tuck (neither looked good). My parents came downstairs to find the pair of us geared up, beaming, with our elbow pads on the wrong arms.

I had no idea that I stumbled on the thing I wanted to spend the rest of my life doing. As soon as I started playing hockey, I couldn’t remember a time when it wasn’t a part of my life. It became my answer, my purpose. To learn hockey was to learn pain and passion as one. I was learning about myself. Who I thought I was; who I actually was. I was creating proof of my place in this world.

But this all changed on a Thursday evening in 2023.

The air smelled like autumn, but I wasn’t putting on my hockey skates. My therapist bluntly informed me that no athlete handles retirement well.

Grief is not the right word for it. It feels less like sadness and more like emptiness. What I’m facing now is a new opponent. I had a coach once tell me, “We are our own biggest enemies.” I am facing myself, now.

These are some memories I lean upon. Moments that ring clear and true through the noise, that teach me new lessons each time I revisit them.

I’m four or five, and the winter is cold. My family is at the local outdoor rink for a skate-around. In the early morning, since the fence is high along the boards, the sunlight streams through in dashes. I must be learning to skate (or at least learning to glide upright). We play the game where my dad skates backward and pulls me as fast as he can before letting go. The giggles are tremendous. I tell him, quite sincerely, “Dad, one day I want to skate just like you.” To my surprise, he laughs. “I hope not,” he says, “Reach higher.” He teaches me that potential is not always visible. Our limits extend far beyond what we can see.

Twelve years later, my team is at the Final Four Junior Championship Weekend for the second year in a row. I know that through my hard work and as the veteran goalie this season, I have earned my opportunity to start in the first game of the weekend. Only, I don’t get that opportunity. Instead, I learn about resilience. I learn how to be steady in the face of adversity. I learn how to advocate for myself and how to respectfully enforce and communicate my boundaries. If you’d asked me at the time, I just wanted to play. Later in the weekend I get my chance, and I learn another thing: I am right to believe in myself.

As I stumble out of the rink after playing my hardest, I see my mom waiting for me in the lobby. She has purchased a hockey card of my favourite goalie, Carey Price. She hands it to me. She has never doubted my capabilities. She holds the door for me as I go to battle. I believe the love we are surrounded by when faced with adversity can save our lives. I carry that love, and that card, with me today.

Especially in the formative years of my childhood, hockey represented everything good the world had to offer. At Yale, something changed.

There’s a heaviness around it all, now. A feeling of dragging myself back to memories that don’t follow me the way memories should follow. A feeling of helplessness when I try to write about it. How can I write about something I can’t remember clearly?

The way the brain works: disjointed. Memories of one thing, then memories of the same thing that feel different. No map to connect them.

For example, in my Sophomore year at Yale, I played in a game against Quinnipiac (a big rival) in our home rink.

Memory One: The deep brown wood of the ceiling crowns around us and darkens the stands. Richly coloured banners of Ivy League schools crest end to end like teeth. The ice is hard and fast. I lean on my left foot while the puck is in the other end. On a whistle, I turn to look in the stands, and I see my parents and family friends who have all come to support me. I smile and feel a warmth inside me.

Memory 2: I look into the rink glass and find my own eyes. I peer over my blocker-side shoulder and see my family waving and cheering me on. I make 37 saves, and I don’t remember any one of them. I don’t remember how my team reacts after the buzzer, nor can I think of anything my coach says to me. I’m certain there are happy moments here, yet I can’t find a door to them. I walk down the hallway from our locker room to dinner. I feel heavy. I feel empty. There is nothing left in me to celebrate the victory we had long strived for against this rival.

Losing hockey happened slowly. Hockey ceased to be the feeling and started to be the memory of the feeling. I worried that the people around me saw my light begin to dim.

It’s hard for me to pull the strings apart, even now many years later. I’m bombarded by that same blankness which seems to penetrate even the most innocuous memories from college hockey. Everyone struggling at once, but not together. The camaraderie and support that usually defines the locker room does not seem to reach me here. During my exit meeting after my first season, the coach informed me to watch my back because there is an excellent first-year goalie coming in. Just as conditional love is not love, learning through fear is not learning.

These memories do not revive themselves in order. Picture it like this: my head is always underwater but with a thousand small breaths of air. Each breath, a fountain of relief. Or like this: always the moment before falling but never the fall, itself.

Eventually, I graduate.

Then, I’m drafted by the NWHL! A new team, a new place, no school—life is good. I eat through my savings. I work out in the middle of the day and skate all the time. We travel to Lake Placid for a bubble season, and after so many months without hockey, I finally get to play again. Our team is full of leaders, and the atmosphere they help create is competitive and welcoming. That feeling post-game is something I have forgotten hockey can make me feel—elated. Our season is cut short, but it has sparked something in me that I didn’t think was ever coming back.

I play for Toronto my second season. I’m determined to prove myself, and I do everything in my power to be at the top of my game. My teammates are hard-working, and they push me. I’m excited to be there. I feel whole again in so many ways. I wish to play more, but I take the opportunities I get. I work hard to stay positive.

Then, I am not asked back. I try out for Buffalo. I’m brought on as a practice goalie. I have used up all my savings, so I get a full time job and commute back and forth for practice after work—4 hours round-trip. Eventually, I am signed on full-time, though I am still making too little money as a hockey player to even relocate. I get more and more tired as the season continues. Suddenly, I’m back in the blankness. I need to pull myself out.

We called it an upper body injury. Is the soul in the upper body? Either way, I extricate myself from what I did not realize would be my last season of professional hockey. It was the smartest and hardest thing I’ve ever done. It was exactly what I needed, and yet, not what I should have needed. Not what I wanted to need. What I wanted was to continue to play, to be surrounded by my team, and to be connected with my sport. But I could not have all those things at once because of a system that wasn’t robust enough to support us. Our league experienced a lack of funding, a lack of investment, and a lack of media attention. It’s hard for any individual to persist under those conditions let alone a whole organization. The conditions that many non-male athletes face in professional sports are a ripe backdrop for burnout, or worse.

I’ve stepped away now, from playing hockey. Though I wanted to continue, I was not provided an opportunity to enter the new version of our league, called the PWHL. But as I journey forward and find my footing (slowly), there are others who continue to trod along under some of the same difficult conditions. My hope for them is that they are getting the support they deserve. That is how the sport will grow. It’s time to find new ways to reduce barriers for athletes. While I would have loved to be a player in this new iteration of professional hockey, I am not. So my path will be different; although this is still hard some days.

Every time I step onto the ice, I move more towards my identity. This has been true for me since I was a young girl. Over my many years in the game, though, so much has worked to push me away, too. From harmful learning environments, to under-resourced teams, I’ve been forced to sit in the puddle of someone else’s idea of my sport just to have a drink. I’ve been faced with numerous challenges, though never with the challenge of leaving. Perhaps it’s the right thing for me, or perhaps I will have to find a way to make it the right thing.

What I do understand is that while I face this new opponent named retirement, I have a hopefulness in me. Through hockey, I’ve learned new ways to love and be loved. I’ve learned over and over again how to succeed when faced with challenges – and more importantly, how to navigate some of those stronger, nameless emotions. Healing comes from a place of self-power, not self-control. I’m fortunate now to have a team of my own selection to help me through this journey: the people I love most in this world. Once, my job was to play hockey, now my job is to heal from hockey. I will do this so I can come back to it feeling revived, and so I can help the next generation of players access the sport they deserve.

Comments ()