Former New Zealand Captain Dr. Helen Murray Continues to Lead With CTE Research

New Zealand's own Dr. Helen Murray continues to break new ground on the ice and in CTE research.

Dr. Helen Murray has become an industry leader in a relatively new branch of neurodegenerative research while playing the sport she loves on the international stage for New Zealand.

While she was always interested in science and studied Alzheimer's disease at university, she attended a talk on CTE during a school holiday that would ignite the beginning of what she says will become her life’s work. "Literally a light bulb moment," she calls it. "This is what I need to do with my career."

At age 33, Murray has already spent a decade seeking the root cause and biological links between repetitive head injury and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) while balancing an ice and inline hockey career at the local and international level for New Zealand.

Murray’s vision is that her research will help lead to a world where we can get an MRI or a blood test to accurately diagnose brain injuries and prepare a supportive care plan before symptoms even occur.

But before diving into her fascinating discoveries and their possible applications, let’s take a look at Murray’s athletic career.

Women's Hockey on the Rise in New Zealand

Murray's family started playing inline hockey together when she was 10, but she decided to transition to ice hockey when she felt a little more interested in the sport. For several years and through university she played both ice and inline hockey. She had her international debut with the Ice Fernz (the official name for Team New Zealand), in 2013 when the country hosted the Division IIA World Championship.

The tournament sparked the formation of a three-team domestic league, the New Zealand Women's Ice Hockey League (NZWIHL) to help the Ice Fernz develop. One of those teams is the Auckland Steel, where Murray played as forward and their captain for the next eight years. She also captained the Ice Fernz through five of her nine international tournaments.

Women’s hockey continued its rapid growth spurt with the launch of their girls’ U18 team and a fourth team joining the NZWIHL in 2020. According to the IIHF there are now 480 registered female players in the country. As a cherry on top, the U18 team won their first gold medal at the 2024 World Junior Championships in January, earning them a promotion to Division IIA. Needless to say, hockey seems to have the Kiwi seal of approval.

It's not surprising that hockey would thrive in a country whose national sport is rugby. “A lot of people are pretty hockey-mad,” Murray confirms.

As is common with most new hockey leagues around the world, New Zealand hockey players travel hours for a single training session and self-fund most of their competitive endeavors. “She sold her horse,” Murray laughing about one way a teammate fundraised for Worlds. “She said it wasn’t being ridden much anyway.” Murray goes on to appreciate the country’s support surrounding hockey, both as a tight-knit group of players and the greater New Zealand community.

With fewer than eight indoor ice rinks in the entire country, nearly all U18 and senior team men’s and women’s players have played together or at least know each other. When one group leaves for a tournament, they all motivate and celebrate each other’s achievements. As for the larger community, the teams often ask the same people year after year to help them get to international competitions, but Murray says they help every time. Even more, this direct connection helps the Ice Fernz feel anchored to New Zealand during tournaments.

"Not only do you feel like you’re playing for yourself and your country but you’re also playing for all those people who have stepped in to help you fundraise and get you to where you are, so that’s probably one of the most special things." Murray continues, “I still get teary eyed when I hear my anthem…even ten years later.” Although COVID took New Zealand out of international competition for a bit and slowed its development, Murray hopes that hockey will ramp up again soon and that a fifth team might even join the New Zealand Women’s Ice Hockey League in the future.

We talked more about her personal experience playing internationally in the second division. Murray notes how every country approaches the game differently: “You never know what you’re going to get." She adds the Ice Fernz have played against Iceland enough times to develop a small rivalry with their fellow small volcanic island. She pencils in South Africa as one of her favorite places she’s been able to travel for hockey, because the team decided to make the most of their trip and go on a safari.

When Murray was asked why she loves hockey, her answer is what one would expect from a team captain, elite athlete, and scientist: “There’s always something to learn.”

She elaborates, "Whether you come in as a junior and you’re learning how to play, whether you’re a senior and you’re learning how to be a leader, learning how to mentor - there’s so much from hockey I think I’ve learnt and carried over into life and research." The quote wonderfully sums her up history thus far: her rise from player to captain and then confidently passing the torch to the next leadership group for the Ice Fernz while at the same time advancing in her research career to leading her own team of PhD students.

Safer, but Not Stopping: What Murray's Research Means for Sport and Beyond

Discovering and presenting ground-breaking research that could help revolutionize neurodegenerative brain treatment is a pretty good reason to miss a World Championship. When I first scanned the New Zealand roster for potential interviewees, of course a player who’s also a neuroscientist piqued my interest. After watching her presentations, I felt her story was particularly relevant with the addition of checking into the women’s game.

So, what does the science say about CTE?

According to Murray there’s just not enough of it yet - which is part of the problem. Most the research is about 10 years old "so it's completely untapped; we just don't know anything about CTE," Murray states.

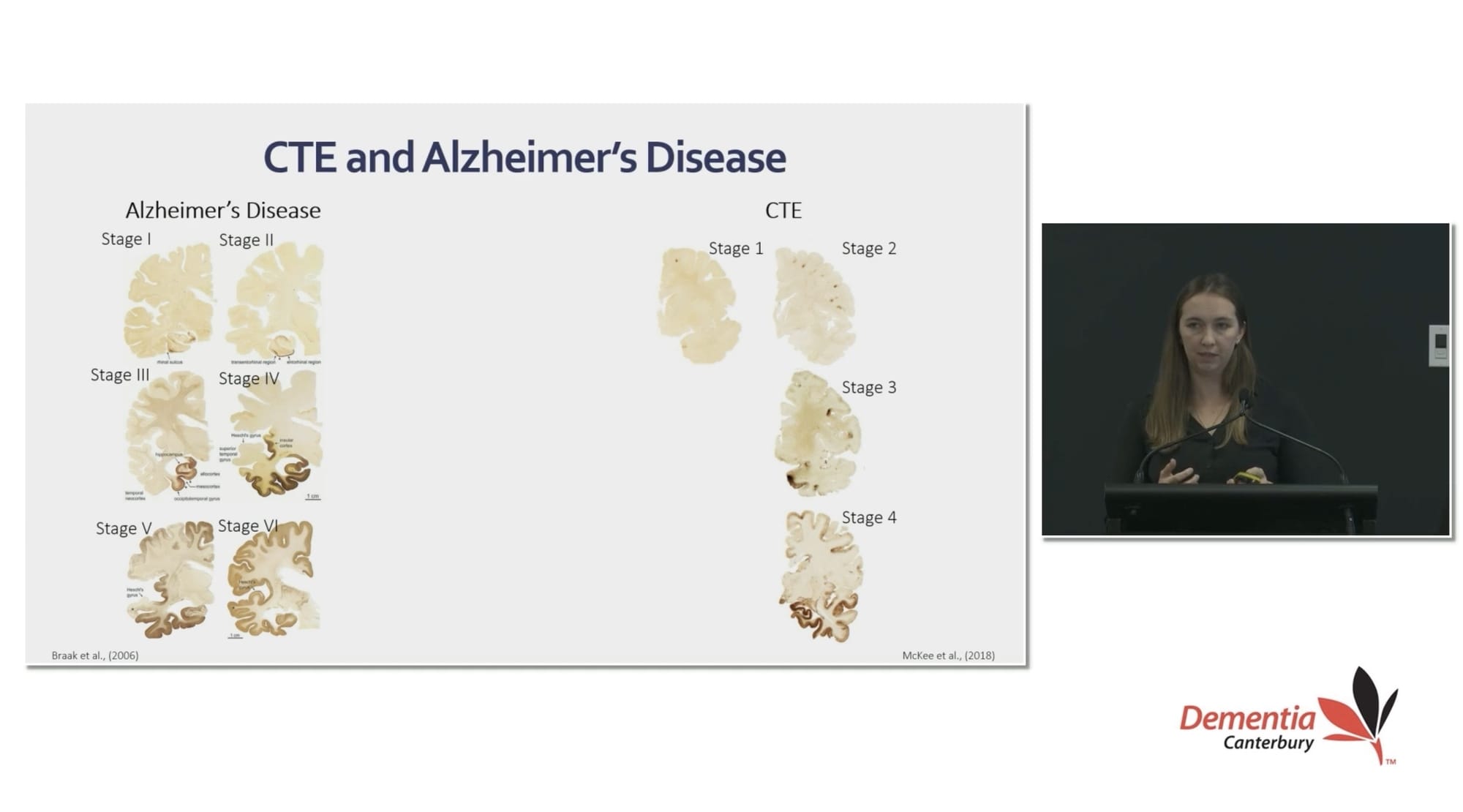

She summarized the state of CTE research during a 2023 Brain Health conference in New Zealand: dementia is an umbrella term for neurological conditions that lead to cognitive decline over time; CTE and Alzerimer’s are examples of these conditions. However, less than eight studies (out of only 104, which Murray says is “barely anything” in scientific research) look at inflammation or blood vessel damage in brains given a CTE diagnosis postmortem. In other words, almost zero research examines the unique brain tissue damage of CTE, while Murray says Alzheimer's has “tens of thousands” of studies for comparison.

“It’s information we just have to have,” Murray campaigns to an audience during a 2023 Brain Health conference. She continues, stating that without it, we cannot create good diagnostics, treatments or preventative strategies.

She connects personally to her research, saying, "a lot of the women I play hockey with have unfortunately had to stop playing because their concussions have gotten so bad that they now have long lasting effects from it." By seeing the detrimental symptoms up close with her teammates, Murray is determined to figure out how to mitigate CTE risk and what can be done if it does develop.

In our interview, she said, "people know that I'm not out to get any sport. I absolutely love my sport and it is a contact sport." On the contrary, she believes more investment into research and understanding the causes may actually keep people in sports longer.

“It’s not necessarily about the number of concussions, it’s about the number of head impacts.” - DR. HELEN MURRAY

At this stage of her research, Murray and her team affirm repetition as a key variable in developing CTE and more scans of diagnosed brains could generate even stronger evidence for this theory. As Murray says, “it’s not necessarily about the number of concussions, it’s about the number of head impacts.”

Murray provides an example from her own playing experience. After she scored a goal, she tripped and fell right into the boards, but she thought it didn’t feel or look that bad: maybe just "awkward." After the game she felt tired, but wasn't sure if it was from the impact or from fatigue. Then, over the next few days she felt foggy but said her symptoms would not register on a concussion test.

A startling discovery prompted her to reevaluate: "I looked at my helmet and my helmet was broken." Out of an abundance of caution Murray decided it was best to sit out the next training and let her brain recover. Before her research, she said she wouldn’t have given it a second thought, but she knows not every impact will produce concussive symptoms. "Even though there are these processes involved to protect us, we need to take a bit of a personal approach to it as well."

This is part of why level of play is not a critical component of being at risk for CTE. Professional athletes could get concussions and not develop CTE and amateur athletes could get CTE without having any concussions. What matters is cumulative repetition of head impact.

Since head hits only receive medical attention if the athlete is exhibiting egregious symptoms like dilated pupils or being unconscious, I asked her thoughts on the current state of head injury care and how it relates to her research. Murray says she hopes her research can potentially lead to tangible ways to diagnose brain degeneration early and bring more awareness to athletic stakeholders and athletes themselves. "When we talk to people who have suspected CTE, what they've all told me, 'I just wish I knew what this was. I want to understand so I can do something about it.' They don't have that option right now, people just telling them, 'oh you've got depression, you've got something you can modify,' and actually, it's a form of dementia."

Fortunately for her, she says the New Zealand sporting groups are in agreement with the research and want to prioritize player welfare. “How do we make sure players have great careers and then happy, long, healthy lives.” She knows it's a contentious topic globally, which is why she is determined to contribute to the research. Although there is no cure, currently, generating more awareness from athlete’s themselves to self-evaluate may be the first step to large-scale mitigation, "it's the hope piece," she says, "knowing people are trying to figure it out has been quite important." I inquired further about how she thinks athletes should be involved with their own health decisions.

"We're just built different aren't we?" Murray begins, getting me to chuckle, "literally being an athlete is pushing your body to the limit." She shares an example of a teammate who played through Worlds with a torn ACL because once an ACL has fully torn and needs to be reconstructed, you technically can't make it "worse." But she says we need to take more caution with head contact because we have no way to “stitch up” and repair the brain like a torn ligament.

“We’re just built different.” -DR. HELEN MURRAY

Stories like the ACL tear are all too common in sports, certainly in ones like hockey. We all know the infamous list NHL teams release after playoff elimination describing the brutal injuries some players skated through which is always followed by the peanut gallery's applause for "toughness." Since professional sports are what's on television, that's what youth and amateur athletes are seeing and then replicating. Kids try and play through any injury because ‘that’s what the pros do.’ Luckily, the Ice Fernz have years of leadership from Murary who demonstrates taking accountability for her long-term health after elite level sport.

One might assume Murray would play less knowing the science behind the risk, but she says she will playing hockey for her entire life. "Regardless of competitive or not...hockey will always have a place in my life." However, when she wears the "A" for the Auckland Steel and plays socially, she's more cognizant on the ice and aware of how she feels after a hit. "Be mindful of all impacts," she says, "really feel how you're feeling and be honest with yourself."

She also advocates for youth players to take a break to let the brain heal from any in-season contact. "It's good for reducing head injury exposure, it's good for allowing your brain to recover, I think actually having an off-season is something I value more and more."

Overall, in the case of CTE risk mitigation, knowledge is power.

Athletes are constantly being pressured to play at all costs and many team captains are adorned for their ability to push through injuries. But maybe sitting out is the braver choice a leader can make. It demonstrates to teammates, especially younger ones, that long-term health after sport matters. "Be courageous," Murray says, and take a rest if needed.

Murray is a shining example of the incredible stories of passion and dedication sprinkled throughout women’s hockey. Without many resources and funding, teams and players from all around the world find a way to compete at the international level while balancing jobs, families, and school. Her CTE research journey is such a unique and meaningful way to give back to the game and the discoveries she and her team make will benefit anyone involved in sport.

Murray concludes, “everyone's still here for you. Hockey will still be here for you. Come back when you're happy and healthy."

If you are interested in learning more about the research, here is the full-length video of the Brain Health Conference discussed throughout the article. It's easily digestible and covers the scope of what CTE is biologically in the brain, her specific research and what the future holds.

Dementia in Contact Sport Athletes from Dementia Canterbury on Vimeo.

Comments ()